|

Archaeology

WOOD

AND WOODWORKING IN ANGLO-SCANDINAVIAN AND MEDIEVAL YORK WOOD

AND WOODWORKING IN ANGLO-SCANDINAVIAN AND MEDIEVAL YORK

by Carole A, Morris PhD

(paperback) 408 pages, B&W line drawings throughout, B&W and colour photos (2000) Out of print - temporarily unavailable This report presents over 1500 domestic and utilitarian

artefacts made of wood from six locations in the city of York - including

complete objects as well as woodworking waste, unfinished products and

woodworking tools. The date range covered by the assemblage is c.850-post

Medieval. The bulk of the material is of Anglo-Scandinavian date (c.850-late

11th century) and was recovered from excavations of well-preserved structures

and associated features at 16-22 Coppergate, the Coppergate Watching Brief

site and a site excavated in 1906 at the corner of Castlegate/Coppergate.

Medieval material from those sites and from the College of the Vicars

Choral at the Bedern, the Bedern Foundry site and 22 Piccadilly is also

included, as is a small amount of late-post Medieval material from some

of the sites. Taken together, these sites produce a very detailed picture

of the production processes of many different types of wooden artefact,

but especially those produced by lathe-turning, and the many uses of different

forms and species of wood in the daily life of the people of York over

a period of nearly an entire millennium.

The report includes a brief description of the sites from which the material

was recovered, and the material itself. This is followed by a discussion

of the particular conservation techniques used to preserve these wooden

assemblages, and of the specially-prepared wet wood laboratory and equipment

developed to cope with the conservation of waterlogged wooden objects

varying from several centimetres to several metres in length! On-site

retrieval, temporary storage, conservation, reconstruction and permanent

archive storage of the artefacts is discussed.

The rest of the report presents the material

in two main sections. The first section, 'Craft and Industry', describes

and evaluates the evidence for the production of wooden objects. This

involves not only the exploitation of local woodland, various types of

woodworking tools and general woodworking techniques, but also the two

major vessel-producing crafts of lathe-turning and coopering. Most of

the excavated evidence is for the manufacture of lathe-turned wooden bowls

and cups during the Anglo-Scandinavian period at 16-22 Coppergate in the

form of part of a lathe, roughouts, unfinished discarded vessels, waste

products and an iron turning tool. Possible locations of turners' workshops

in Coppergate are discussed and their craft linked with the street name

'Coppergate'' - 'the Street of the Cup-turners'. Coopering is mainly represented

by finished products.

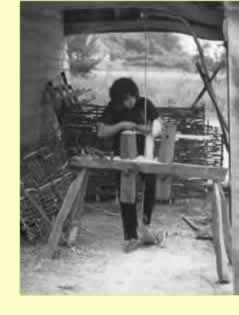

(image

on right) The author turning a wooden bowl on her pole-lathe (outside

Bayleaf house) at Weald and Downland Open-air Museum at Singleton

(for

more about the Bayleaf project) (image

on right) The author turning a wooden bowl on her pole-lathe (outside

Bayleaf house) at Weald and Downland Open-air Museum at Singleton

(for

more about the Bayleaf project)

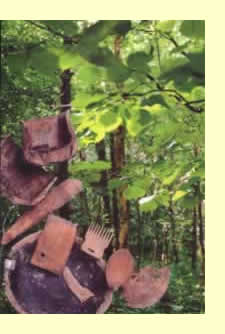

The second section, 'Everyday Life', presents the extremely

wide range of wooden artefact types which were not necessarily made on

the sites under discussion, but which were used (and discarded) there

for a variety of functions. These include domestic equipment and utensils;

boxes and other enclosed containers of various sizes and shapes; furniture

such as garderobes and stools; personal items such as pins and combs and

wooden-handled knives; manual and agricultural implements from spades,

shovels and mattocks to parts of a plough; implements used in the manufacture

and handling of fibres and textiles, artefacts used in other non-woodworking

crafts such as leatherworking, riding, the handling of ropes and cords

etc.; wooden components of games and pastimes such as gaming boards and

parts of musical instruments; small wooden components of internal or external

structures such as roof shingles, window openings, door latches and panels;

pegs of various kinds and re-used boat timbers; and miscellaneous wooden

artefacts whose uses are as yet unidentifed.

Finally, a short discussion attempts to bring together various

general conclusions from the study of this material.

A catalogue of all the wooden artefactual material recovered from the

sites and a provenance concordance completes the report.

Reviews

Since James Graham-Campbell's 1996 review of the path to

publication of York's Anglian and Anglo-Scandinavian archaeology , much

has happened. Tweddle, Moulden and Logan's important synthesis of Anglian

York (AY 7/2) has provided a much needed review of the background to the

more widely known Anglo-Scandinavian archaeology, whilst Richard Kemp's

report on the Fishergate excavations (AY 7/I) has provided a detailed

view of the physical aspects of Anglian settlement. Perhaps the greatest

achievement of the York Archaeological Trust, however, has been to bring

to publication the majority of the material derived from the Coppergate

excavations so ably directed by Richard Hall between 1976 and 1981. Volumes

on other materials, including pottery (AY 16/5), ironwork (17/6) and,

more recently, bone, antler, ivory and horn (AY 17/12), are already established

as invaluable catalogues for students of early medieval material culture.

The volume reviewed here follows the format of the latter, as an A4 monograph

facilitating more extensive visual representation of the subject matter

of each.

Carole Morris's volume on the objects ofwood and the evidence

for their manufacture is a splendid production which allows the nature

of occupation of an earlv medieval town to be viewed alongside the material

culture of other European towns where waterlogged deposits have preserved

an array of objects not normally preserved in the British Isles. Indeed,

the range, if not quantity of wooden material culture compares well with

that from Novgorod. The volume is divided up with the first section detailing

the evidence for woodland exploitation, woodworking tools and techniques,

lathe turning (finished and waste products), fragments and offcuts and

coopered vessels. The second section considers domestic equipment and

utensils, boxes and containers, furniture, personal items, agricultural,

textile working and other tools, games and pastimes, structural finds,

pegs and miscellaneous objects. The incorporation into the book of much

of Morris’s Ph.D. research makes for an informed study of much more

than regional import, for this is a research volume of international

importance. The breadth and depth of research is impressive as befits

the material with which it deals (see for example the discussion of ‘Building

Accessories and Structural Fragments'). The author’s own experience

of working with her chosen material is evident throughout the text, and

a rare combination of both practical awareness and academic approach is

achieved. Despite the overall emphasis on the pre-Conquest archaeology

of York, Morris's volume contains a good deal of material from later medieval

contexts, including ‘probably the most perfectly preserved complete

medieval bucket found on any site in Britain' (from early 15th-century

levels at Coppergate).

Overall, the presentation of this volume is of the highest

standard and the price is very reasonable. The illustrations are excellent,

particularly of the wooden objects (largely by Kate Biggs) The overall

style and quality of presentation, including the eye-catching cover design,

makes this volume a pleasure to handle and use.

Andrew Reynolds

Abridged from review published in Medieval Archaeology 45, 400-401 (2001)

Being old, tired and past it these days, it takes quite a lot to bring

a smile to my poor sad old face. This book managed it. My interest in

wood and woodworking obviously means that I am biased - but what an

achievement this book represents. There is a certain amount of solid

archaeology for those who need or want it, but there is an awful lot for

normal people as well.

Instead of grouping finds together according to where they

were found, Carole Morris groups them according to what they are and what

they do. After relatively short sections on the archaeology and conservation,

she gets down to looking at material under two main headings: Craft and

Industry and Everyday Life. The first section deals mostly with techniques,

especially turning and coopering, and tools. The second section brings

us glimpses of ordinary people doing daily tasks: wooden spoons and spatulas,

buckets and knife handles, boxes and lids, bits of furniture, lavatory

seats, combs and fragments of musical instruments.

So who will enjoy this book? Wood and woodworking specialists

are a small but obvious group of readers. Any modern craft worker,

however amateur, would be fascinated by the glimpses of these ancient

crafts. The archaeological material is beautiful (and beautifully

drawn), and illustrations from early manuscripts show this material being

produced and used. Instead of pages and pages of pottery or animal bones,

we find ourselves looking at door latches and spades, rakes and ploughs,

wooden pins and part of a beautifully decorated saddle. Anyone who has

tried to imagine how people lived in the past will find plenty to flesh

out their imaginings here. Although written for archaeologists it will

appeal to anyone who is interested in life.

Maisie Taylor (a specialist in ancient

wood based at Flag Fen)

From review published in British Archaeology 58 (2001)

www.britarch.ac.uk/ba/ba58/book.shtml

Excellent

book for woodworkers Excellent

book for woodworkers

This is an excellent text, especially

for woodturners interested in documenting period styles. At 450 pages,

this beautiful book contains an amazing amount of detail concerning

the wooden artifacts that have been found. As the focus of this book is

on the artifacts dating from the 10th through 15th centuries, there is

an impressive amount of interest to SCA [Society for Creative Anachronism]

woodworkers.

This book should be of even greater interest to woodturners, as it has

one of the best sets of diagrams showing period turned bowls and cups

that I have seen, including inner and outer profiles. You can see a small

sample here. In addition, there are multiple section on technique, including

use of a bow lathe, methods used for making cups and bowls, and even how

they would cut and use logs for various projects.

There is simply such a wealth of information in this book that I can't

begin to adequately list its contents, but an abbreviated list of highlights

include:

Woodturning forms, tools and a discussion of their use.

Cask, barrel and bucket construction, including the only intact well-bucket

from this period known.

Wooden spoons, spatulas, pot lids and other domestic woodware.

Boxes, including lathe turnes boxes.

Wooden game boards and pieces

Garderobe seats (yes, really).

Breakdown of wooden items found by type of wood.

If you have any interest in Medieval woodworking, you must get this

book.

Glenn Basden Sacramento, CA, USA

Reviewed on Amazon.co.uk:

23 March, 2001

|

Archaeology

Archaeology

Archaeology

Archaeology